Clarion Vol. 1: Kandis Williams: A Line

Magical First Equipment

Excerpt:

Dance is the most ephemeral of the arts because the human body is the most ephemeral of media. In the centuries before film and photography, choreography could be preserved only through imitation and apprenticeship—more often, it was lost entirely, surviving only as anecdote. Unlike painting or sculpture, dance had no material existence outside of the body; unlike music, it had no system of notation. Until the invention of Labanotation in the early twentieth century, there was no inscription system available to preserve choreography as an inheritance. In this evanescence, dance as an elite art form sharply contrasted with Indigenous, African, and folk dances, many of which were transmitted across generations via a thick social weave of repetitions. . . .

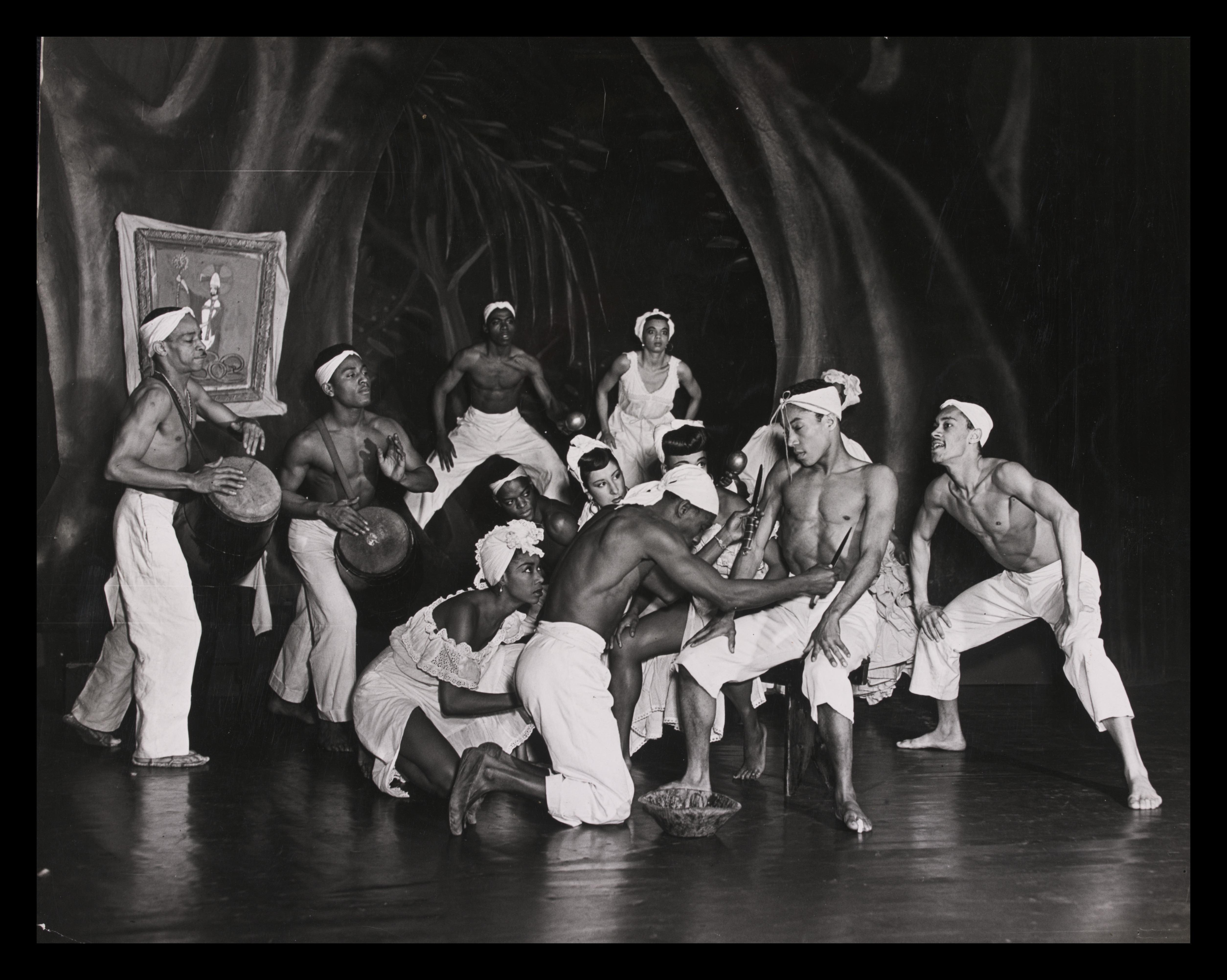

Black artists turned the fantasy of the primitive to more constructive ends, following a principle of cultural survivals rather than discontinuity with the past. The American dance artist Katherine Dunham 1 went to Haiti to learn ritual dances of African origin, synthesized in the impossible conditions of the plantation and further developed in its revolutionary aftermath. Dunham felt this was movement that still retained its social power: the power to maintain life and ritualize conflict. She looked to its forms as antidotes to ambient anti-blackness in the United States. These embodied mechanisms of social integration offered, she thought, communal protection against the perception and imposition of blackness as a state of disintegration. The plantation, more than any other social form, inaugurated modernity—C. L. R. James called the slaves of the Caribbean the first modern proletariat in the world, just as W. E. B. Du Bois named the slave uprising that won the Civil War for the North the first general strike. 2 Blackness is the vanguard of the modern, and Dunham’s impulse was quintessentially modernist in its desire to access a prior condition of unmediated, collective experience.

It does not seem merely coincidental that ballet emerged in the same time and place as the capitalist world economy, in fifteenth-century Italian Renaissance courts. The corps de ballet 3 (body of the ballet), a somewhat later innovation, is a mass of identical dancers performing identical movements. The corps anticipates the chorus line and the factory line and implies the line of race. After abolition, the encounter between the courtly European formalism of ballet and black vernacular dance produced the distinctive character of American modern dance.

Katherine Dunahm’s ballet Shango, from A Caribbean Rhapsody, at the Royal Court Theatre, London, 1947. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America 1860–1880 (New York: The Free Press, 1998).

Corps de ballet of the Mariinsky Ballet in Swan Lake, 2012. © Gene Schiavone